Nothing like leaving travel plans to the last minute. But with the help of Winnie, our travel agent in Hong Kong, we manage to book a holiday package to Bali and our tickets will arrive tomorrow afternoon.

This morning, the British, American and Australian governments are all warning their citizens against traveling to Indonesia, citing “credible evidence” of a planned terrorist attack against westerners. Hmm…Bali is in Indonesia, it has been bombed before, Leela has a British passport and I’m American. Not good. I email Winnie.

Winnie calls to say our package cannot be changed. I counter with credible evidence that we will be on her conscience if anything happens. She send us alternatives. We pick Khao Lak (pronounced Ko Luck), Thailand.

Winnie books our air tickets and will confirm Le Meridien Khao Lak Beach Resort and Spa on Monday, leaving me the weekend to look for the Deep-Tanning Carrot Oil and my swimsuit.

Confirmation received. We fly out Thursday at 1105.

Last day at work so naturally I get home late and packing lasts until midnight. But contrary to my usual “take everything you’ll ever need” style, I pack a single roller case and a camera bag, as does Leela. By 1am, we’re asleep.

Up at 0700, in the taxi at 0830, at the airport at 0920, in Phuket at 1340.

The “45-minute trip” to Le Meridien takes 75 minutes in a high-speed Mercedes. When we arrive, we step into an open-air lobby 100 metres from the beach. After check-in, a young lady takes us to room 385. As I’m climbing stairs I’m wondering if I should ask for a ground-floor garden room, but when I walk through our door I forget to ask — it’s beautiful, which you can see even from the bathroom because there’s only a glass wall between the two. While you’re soaping up or drying off, you can watch TV in the living room and see the balcony, palm trees and blue sky beyond.

Before I can relax, however, I must stop the screaming. It sounds like a high-speed drill bit being forced through steel without the benefit of Carrot Oil. I look over the balcony, search along the corridor and walk down to the lawn, but I can’t locate the source, so I give up and have a cold drink.

Late in the afternoon, we slip on our flip-flops, grab our cameras and walk along the beach towards the setting sun. Later, I’ll realize this is a reconnoitre that will come in handy, but for the moment we enjoy the sun, sand, surf and each other. The screech is even louder here and we realize it’s coming from the trees. There is a mutant breed of supersonic cicada that is definitely not like the cicadas back home. Instead of the familiar eee-ooo-eee-ooo that occasionally goes silent before starting up again, this is a full-bore, non-stop "I want sex!” scream. I hope they find love soon.

We stroll as far up the beach as we can before high tide stops us at the rocks. As the sun sets, we discover wooden stairs half-hidden in the bushes that take us up to Similana Resort. We climb past wooden bungalows perched on the cliffs facing the sea. They’re lovely, so I pick up a brochure at reception. In the dark, we walk down the far side of the hill and one and a half kilometres out to the main highway. We turn left for another two kilometres to Le Meridien, and then a kilometre in to the resort and dinner under the stars.

Our first morning in paradise and I discover The Buffet. Breakfast begins at 0630 and goes to 1100 when it gradually changes into lunch that lasts until 1400. Seven and a half hours and if you’d like to just eat your way through your holiday, you’re welcome.

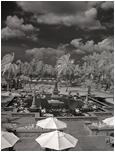

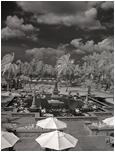

We sit down at 11am and two hours later I’m attempting to tan off my meal by the pool.

The staff invite us to the Christmas Eve party tonight, but I’ve eaten so much that I’ll hurt myself with dinner, so we pass. Instead, we explore the beach again, this time photographing everything that moves, stands still, or lives in small dark holes. At least I do — Leela is more discriminating.

We return to our room after dark with plans to turn in early when Leela spots huge candle-powered paper lanterns floating up from behind the bungalows. There are already twenty in the night sky and they are irresistible, so we dress and hurry down to watch staff and guests send up more. We are in a luminous garden of trees, bushes and grass lit by fairy lights, with lanterns drifting overhead. It is magic.

A band starts playing and Leela asks me to dance. Saying yes is probably the best present I could give her, so I do. But since I hadn’t planned on the dancing gift, I also give her a small leather-bound notebook so she can record her adventures and a portable Chanel No. 5 in case her adventures don’t include showers. She reminds me that we promised not to give gifts, that the trip is our gift, that I shouldn’t be so foolish…then gives me a silk shirt that we’d admired the day before. It is a wonderful Christmas Eve and we go to bed in the early morning.

Back to The Buffet, a wiser man. I eat only five times the number of calories I need to get me through to dinner, then grab the Carrot Oil and revisit my deck chair.

In the evening, we take the bus to town and do our tourist thing. I'm hardly off the bus when I spot a German bakery (it's been a while since brunch) where we have tea and coffee and I taste-test a fat chocolate-chip cookie. Then we wander down side roads, taking photos of rubber trees, food vendors, and huts selling bikinis and CDs. We buy three shells and three wind chimes from a small shop.

Dinner is by moonlight, dessert is by bakery. I buy eight more chocolate-chip cookies that will soon become emergency rations. Back at the resort, the blue-tiled pool below our balcony is so beautiful that we go down and take a few photos. It will never look better.

Boxing Day comes early. The bed starts shaking and from living in California I know it's an earthquake. Leela, on the other hand, thinks I'm acting more juvenile than usual and tells me to stop. I mumble it isn't me and she asks, So what is it…an earthquake? Yes, I tell her, now go back to sleep. She still doesn't believe me because after the tremors subside she jerks around to jiggle the bed some more and I assure her that her performance isn't terribly realistic.

We get up at 0930 to a day that begins like our other mornings in paradise — with blue skies, a brisk shower, coffee for her, tea for me. At 1015, half an hour earlier than usual, we go down to the terrace for breakfast.

Leela likes to begin the day with fruit, and at home I join her. But at The Buffet, I start with an omelette, roast potatoes, baked beans and bacon, preferring to save the fruit to fill any gaps that remain (not likely). Even so, I finish my first course while Leela is still playing with her pineapple and she suggests I go back in. Fully fed and feeling chivalrous, I'm happy to wait, so we're together when everyone starts running towards us.

In the lead is a Chinese man with a camera and I wonder if a celebrity has arrived in the lobby. But behind him is a mother running with her baby and beach boys running with mats. Leela's first thought is shark attack.

We're rising from our chairs, scanning for the cause, when the wave explodes against the lawn, creating a five-metre backdrop to the scene. We have ten seconds to get to safety and spend two of them fascinated. Then Leela scoops up her bag, says, Grab your cameras! and we run for the stairs, the last two people off the terrace.

We're last because our table is front and centre and everyone to the sides has fled. The stairs are thirty metres away, so it's a sprint with two hurdles over fallen chairs. I can't tell you what the wave looks like because looking over your shoulder only slows you down. So I don't see it swamp the swimming pool and lotus pond, consume the patio furniture and umbrellas, or crash through the dining room where guests at the buffet tables and the staff serving them don't see it coming. I don't see it smash through the glass walls of the fitness centre or engulf the children's nursery.

We reach the stairs one step ahead of the water. People have stopped on the first landing, halfway to safety, so it takes a little shouting to move them higher. We get our first look at what we escaped when we reach the first floor and round the corner.

Everything I didn’t see has obviously happened. In a minute the water is three metres deep and the destruction caused by the wave’s assault will soon be matched by the powerful suction of its return to sea level.

There are no bodies floating by, no children to pluck from churning waters. Like a light switch, life is on or off. Those below the three-metre mark either made it to safety or are lost.

Until the water recedes, we are trapped on the first and second floors. Those who survived sit in shock or silence or roam the floor, shouting for loved ones. Two house girls perch on the roof of a bungalow. No one needs our help, so I look for things to photograph.

Walking back to our room, we meet Peter and his mother Jean in the corridor. They were on the beach when they saw the wave coming and managed to reach the stairs. They tell us their rooms were on the ground floor (good use of the past tense). We invite them to join us and they turn out to be perfect companions for a calamity.

While we’re waiting out the flood, Leela finds a pair of slacks for Jean, and Peter and I gather supplies — towels, facecloths and toilet paper from an open storeroom, and two big insulated buckets filled with ice that were left in the corridor. I check the minibar for provisions. Peter accepts a beer, I open a Coke and the women have mineral water. I put the rest of the soft drinks and beer on ice and add the candy bars and canned nuts to our provisions bag.

Every half hour or so, someone comes around to tell us to go to the lobby “so we can all be together.” Tough choice…join a pack of people sitting on marble floors for an indefinite time or relax in a five-star room with cold drinks and pleasant company. We decide to stay.

We tell each messenger that we’re comfortable where we are — as well as one floor higher than the lobby. They’re very understanding (and probably wishing they had a choice) and bring us two dozen bottles of water so we don’t dry up.

Everyone else has followed directions to report to the lobby, so we have the floor to ourselves and we spend the time getting acquainted. Peter and Jean are from Australia — he’s a property developer and she is the mother of five who works in her son’s office. I’m in advertising and Leela owned The Prince of Wales Pub in Hong Kong before she began writing full-time.

When the water goes out, Peter and I go downstairs to check their rooms. We find a hotel iron on the top shelf of Jean’s closet, but nothing to use it on. Everything — desk, table, sofa, chairs, bed, television, luggage, clothing, hangers and soap — has been sucked out to sea. Peter’s room is similar, except that his mattress is still there on top of smashed boards. He does find a matching pair of shoes.

The sliding doors and windows aren’t tempered, so there are serious shards of glass lying about. I turn my imagination to Off and try not to lose my balance in the slippery muck. There is the added concern that the building may have weakened to the point of collapse and the sharp crack of the bathroom ceiling suddenly giving way doesn’t help.

All that remain of their personal possessions are passports and money in the room safes — which we can’t open because their electrical innards are drowned and which we can’t remove because they’re built in. We go back upstairs.

Two hours later, a man comes by to say we’re being moved to higher ground because a second wave is predicted. We're to leave our suitcases in the room and leave the door unlocked because the key cards no longer work. This sounds like looter heaven to me, so I unlock our balcony door and lock the room door when we leave.

Down at the lobby, an assortment of vehicles is being pressed into service for the big move. We don’t see Peter and Jean and later learn they were taken to a temple in the mountains. Leela and I share a Land Rover with a German woman covered in mud. Our driver thinks he’s in the Dakar Rally and we think about dying in a road accident. Surprisingly, we don’t, and we reach Similana Resort a few minutes later.

Except for the lowest bungalows, Similana is high, dry and unscathed. Unfortunately, there is no one in charge and no one at the front desk talks to us or offers us anything. They leave the gift shop open for a little while but soon shut it, and they padlock the bar.

As the day wears on, no Similana guests invite parents with young children or people clad only in swimsuits to share their rooms. And our fellow refugees are displaying all the bonhomie of a pack of wolves, except, as Leela notes, wolves would come over for a sniff. They mark their spots on the wooden floor of reception, the gift shop porch and a lounge area, and settle in. Everyone is alive but no one seems happy about it.

Five of us spend the afternoon hours in the dining room watching for the next wave. It is predicted to hit at 1630, but when that hour comes and goes, we’re told that there’s no way to predict it. So we look for food.

The lunch buffet has been completely cleared except for some sliced bread and marmalade packs which Leela takes up to the parking lot for the children. People look at her like she’s an alien — courtesy seems to have been lost along with lives. An hour later, a young Thai man brings us a banana and some papaya (Thank you, they were delicious).

As night falls, Leela and I abandon the dining room for the more elevated parking lot, taking tablecloths and napkins with us for warmth and some protection from mosquitoes that match the cicadas in size and single-mindedness.

At first, we try sleeping on the concrete in front of the gift shop, but the noise is non-stop. People are pacing back and forth, smoking like crazy, tripping over us and other unfamiliar bumps in the night. Others stand in groups, talking to pass the sleepless hours. One baby is permanently unhappy and shares his distress. Young people who are probably staff break out pints of whisky and have a party that is so loud and goes on so long that Leela decides to ask them to hold it down. I’m not allowed to go because I don’t have the necessary finesse. But by the time she gets to the party circle, she’s opted for a good telling off, and it works — for about three minutes.

Throughout the night, mopeds and SUVs zip in and out, some on liquor resupply runs. One of the boys crashes a golf cart, shredding everyone’s nerves a little more. Physically fit men suddenly can't walk more than twenty paces and urinate a few metres from us. They are soon copied by women who come in pairs.

Similana staff eventually set out bottled water and cases of Coke and orange soda, which we drink and the staff use as mixer. Around 2200 someone manages to boil some eggs and distributes hot eggs to unsuspecting people.

The general manager of Le Meridien drives in to say that it’s safe to return to the resort and that cars and buses will come to pick us up, although it’s our choice — we can stay if we want. This prompts a number of mindless questions: “When will the wave come? How high will it be? Will it be higher than the last one? If it’s half as high as the first one, will we be safe at the resort?”

He says that he can’t predict the wave and assures everyone that if we stay, he knows where we are, he won’t forget us and he will return in the morning to pick us up — causing one belligerent man to stick a finger in his face and demand, “Do you guarantee you’ll return for us?” To which he replies, “Well, I was going to, but I’ve changed my mind.” (All right, he doesn’t say that, but he should.) At this point, I wander away from the zoo. In the end, it doesn’t matter — no cars or buses ever arrive.

Ninety minutes later, he returns to say that it isn't safe to go back to the resort after all and we have to spend the night where we are. Phuket Airport is out of commission, so buses will arrive at 0900 the following morning to take us back to Le Meridien to collect our belongings and we will all be driven to Bangkok. I'm calculating how many sheets and pillows would have fit in his car but he drives off before I finish.

After he leaves, several of the boys rig up a two-way radio using a long metal pole as an antenna and we are able to get in touch with someone — who warns us that the next big wave will hit at 0200. This prompts a discussion as to whether even Similana is safe and there is talk of going higher into the mountains and sleeping in the forest.

Leela and I decide to sleep through the new wave where we are — a compromise between low-lying danger and high-altitude dirt — but sleep is hard to come by, even after midnight. The noise is constant, the mosquitoes are voracious and the mopeds serve as regular alarm clocks, so I take a walk.

I discover an overlooked concrete platform to the side of the gift shop, but Leela thinks it might be better if we stay near the group for breaking news. While we debate how much news this group is likely to come across, a couple walk by carrying two feather pillows and a fluffy white duvet and set up camp on my platform.

An hour later and more news featuring higher waves. Will this be the 200-metre giant that swamps our hill and returns earth to the cockroaches? No one knows, but our duvet-dwelling neighbours aren’t taking any chances and they head for the hills. Incredibly, they leave behind their bedding, including those two marshmallow pillows. Leela and I move in.

Concrete is surprisingly sleepable with a duvet, a little quiet and enough fatigue. And mosquitoes can almost be stopped with enough napkins. Under a full moon and cotton-ball clouds, we manage four hours of sleep.

Rising together at 0630, Leela and I have the same thought — time to move. If transport is arriving at 0900, walking back will put us at the head of the bus line by an hour, with time to clean up. But before we go, Leela has to make the bed, partly out of habit but mostly out of respect. It's always interesting travelling with a Tidy Disaster Person.

On the road, it feels good to be active again. Thirty minutes later we reach the deserted guard post at the entrance to Le Meridien. The swinging arms are open and three muddy mopeds stand abandoned. The water has nearly reached the highway a kilometre away from the ocean. The sun is coming up. There are white clouds in a blue sky and orchids in the trees. The road is grey mud. We walk past two poignant pairs of flip-flops that their owners have run out of as they fled the wave.

There are piles of cars, trucks and tractors in front of the resort, and two vehicles angled inside bungalows. We walk up the slope to the lobby, take the stairs to the next floor and head for 385. There are mattresses, children’s books and drops of blood along the way.

When the wave hit, the water supply stopped, along with electricity and communications. So I know the toilets won’t flush and I enter one of the abandoned rooms to use their loo instead of my own. I am obviously not the last clever man on earth — in fact, there have been several of us with the same idea. I go to another room and make the same discovery. We are moving against the clock so I hold my breath and use it.

When we reach our room, I go next door and enter the unlocked door of 386. I jump from their balcony to ours, open the sliding doors I left unlocked, and walk across the room to let Leela in. Our untouched cases are still in the closet.

I pull an icy Coke from one of the buckets while Leela has a mineral water. I dump all the ice into one bucket and pour four bottles of water into the other. I soak a bath towel and get rid of the day-and-night’s grime. Leela has a quick sponge bath, we change into relatively clean clothes and we’re ready to go.

Leela walks out on the balcony for one last look and sees Peter stork-stepping through the muck on a mission to rescue two room safes. I ask if he’d like a cold beer. He looks at his watch and declines, saying, It’s a little early. The man’s never heard of a breakfast beer? Under these circumstances? I am surrounded by healthy people.

We leave our room open in case they’d like to clean up and promise to see them in the lobby. Then we grab our bags, say goodbye to the still, beautiful room and go to the lobby to get in the Bangkok bus line.

Fifteen minutes later, Peter arrives with his mother. I admired her hat the day before, and Leela lost her own favourite hat in the flood, so my first question is, Where’s your hat? It’s back in the room and Peter’s off to get it, no doubt carrying on a clever conversation with himself about my fashion sense. He reappears with the hat (What a son!) and leaves with his mother. Leela and I settle in to wait for a possibly nonexistent bus.

It’s not long before we hear chopping sounds coming from the other side of the building. Peter and Jean's room safes have been removed from their closets but they can't be opened. No problem, says Peter, I'll take them with us. Sorry, they've been mixed up with another guest's, so we don't know which are yours. What we're hearing are fire axes.

Leela and I are reading when Peter reappears in our lives, asking if we’d like to share their limousine to Bangkok. When I ask how, he says, There are ways. Fine, be secretive, we’ll quiz you on the way. And so begins our 11-hour dash north.

Peter sits up front tending to chores — arranging soggy passports and money to dry on the dashboard, feeding chocolate to the driver so he doesn’t fall asleep at 140km/hour, and performing regular petrol checks. I like a man who doesn’t rest until he crosses the finish line.

Jean and Leela and I share the back seat, watching the scenery flash by. When the earthquake is mentioned, Leela recalls thinking that a resort catering to families should tell parents that the beds vibrate so they can warn their children. That’s good for a laugh. Our driver stays busy fending off Peter’s chocolate bars and keeping the car above 100.

As we drive, we keep trying my mobile phone so we can let people know we’re all right, but we’re five hours out of Khao Lak before we connect. Leela calls her sister and asks her to contact others. Peter calls his brother so he can spread the news that they’re safe. After that, the system is either down or busy, so we give up and wait for Bangkok. Peter and Jean take turns describing the lovely breakfast they had at the temple thanks to staff from Le Meridien, while Leela and I bite our tongues.

We stop for lunch at a large roadside shopping area and wander around their breezy food court choosing our food. For Leela and me, it’s our first meal since breakfast the day before, so it’s especially good. After lunch, Peter and I walk around the corner to the toilets and find the urinals are bolted to the side of the building, facing a garden. It sounds strange but it was nice and I recommend them for all the alleys in first-world countries where drunken boys go to relieve themselves. Then we shop at their giant supermarket, me for snacks and Peter for razors, before getting back on the road.

I spend the afternoon trying to ply my health-conscious companions with chocolate-chip cookies, Double-stuffed Oreos (I’d never had them before but with famine looming, double stuffing seemed the way to go), almonds, cashews, Peanut M&Ms and water. They accept the water. And Peter indulges me by having an Oreo. It seems there are people who can eat just one.

Peter assures us there won’t be any traffic at rush hour in Bangkok and, miraculously, he’s right. He and Jean are booked into The Sukhothai Hotel. When we arrive, the porter takes their small mudbag without raising an eyebrow. Leela and I have more luggage but fewer reservations. The manager is very understanding despite the hotel being “fully booked” and soon finds us a room and even gives us a survivor’s discount.

We’ve lived through the event but know nothing about it, so the first thing we do is turn on the television. The scale of what we thought was a local event is incredible…and it’s still unfolding. We are stunned to see the number of people killed, but in the days to come we will learn that it is only one-tenth the final figure. Aceh and parts of India and Sri Lanka are devastated, and it’s even hit Africa. When the news turns to other events, we shower, ask if the concierge can help reschedule our air tickets, and order room service.

At midnight, we set the alarm for 0830 and retire.

While we sleep, the concierge is busy. He calls at 0715 to tell us a limousine will be out front at 0815 to take us to the airport for our 1050 flight. An hour later our bags are in the boot and we’re in the back of another chauffeur-driven Mercedes. It’s becoming a lifestyle.

At Bangkok International, a representative of The Sukhothai meets us at the curb, loads our bags on the trolley, marshals them through the scanners, and leads us to the counter with the shortest queue. The agent takes one look at our tickets and says they can’t be rescheduled, but when I ask her to re-check she finds they already are. She gives us boarding passes and we leave for the departure lounge. On the way, I get a call from Winnie, our faithful Hong Kong travel agent. She wants to make sure we’re all right and to tell us there will be a limousine waiting to take us home.

We land in Hong Kong at 1500 and board another Mercedes. An hour later, only one day late, we walk through our garden and into our home. It feels unreal, like one more stop along the escape route. We climb the stairs to our bedroom, set our bags down, open the curtains and catch our reflections in the mirror. Outwardly, we look the same.

|